From Information as a Social System to the Rise of Impersonal Epistemic Institutions: Or, From Kings to Bureaucrats - By Samuel Loncar, Ph.D.

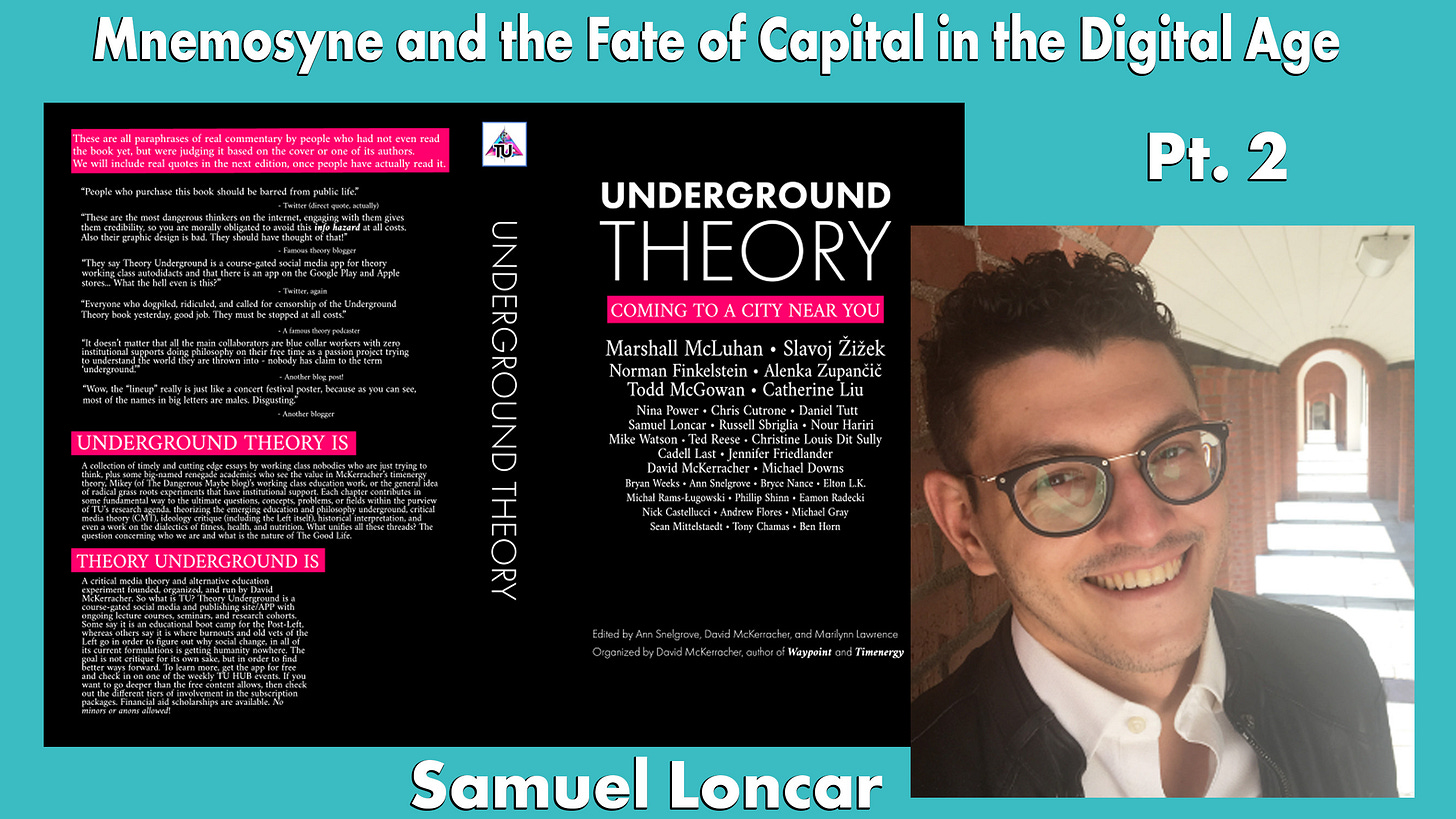

Part 2 of "Mnemosyne and the Fate of Capital in the Digital Age: Ammon’s Law, Technology, and The Invisible Revolution" by Samuel Loncar in Underground Theory

This is Part 2 of Samuel Loncar’s piece in Underground Theory. More info on how to order a physical copy at the end of this post. You can read part 1 here.

III. From Information as a Social System to the Rise of Impersonal Epistemic Institutions: Or, From Kings to Bureaucrats

Tools of information storage and retrieval are features of the technology of literacy; prior to or in the absence of literacy, the only tools of information storage and retrieval are living humans, and to a lesser degree, images and artifacts whose legibility requires the interpretive knowledge stored in particular people, oral experts (the elders, shamans, etc.).

Alternatively, we can now see that literacy enables entire institutions dedicated to and dependent upon complex forms of knowledge creation, storage, and retrieval. I will call these epistemic institutions. These include the obvious institutions, like libraries and universities, but also crucially institutions like bureaucracy itself.

Bureaucracy, viewed as an epistemic institution, is an administrative information system that contains and manages complex functions in which the structure and flow of information rather than the individuals inhabiting its positions determine the nature of the institution. The informational function of a position creates the role’s definition as an officer or functionary of the institution.

As a contrasting example, families and monarchies are highly person-dependent institutions: change of a person signals a crisis moment or possibly a destruction of the institution. Information integrity requires stability, which in turn means ideally person-independent means of storing and transmitting information. If one person leaves a position, the more stable a bureaucracy is, the more it will still maintain its function, simply by replacing the person with another. The role is theoretically unchanged (in fact we know humans affect their roles in bureaucracies, but that is not our current concern).

Human organization can only scale through resilient and effective flows of information, which is why bureaucracy is necessary for any large-scale complex institution, whether a state or corporation, and achieves its definitive form only in the modern world.[i] Such institutions always depend upon intellectual and physical instruments of literacy, which is why bureaucracy has historically always been linked to the scribal/priestly caste of a society.

Our epistemic institutions thus include all institutions, like bureaucracy, that encode and depend upon literate skills, which include the modern state, accounting practices, etc. But bureaucracy could be seen as the crucial enabling institution of advanced literate societies, because it is the material substrate, institutionally speaking, of all significant specialization.

Specialization of functions requires a balancing coordination of complex functions because roles and functions cannot have, by their nature, the additional task of communicating and coordinating with the rest of the institution. Coordination of the complex functions of an institution thus becomes its own position, namely, that of a manager. Managerial authority scales as the direct function or system upon which managerial authority operates is itself a coordinating function. So, a low-level manager manages a small-team, but is managed by a section manager, who is in turn managed by a higher-level manager, until the head of the institution is reached, someone who directly manages the other members of the C-Suite or, in government, the cabinet or its equivalent.

Bureaucracy is thus the literate institution par excellence, and as the technology of literacy changes, so does bureaucracy. Computers and the Internet are in the process of revolutionizing bureaucracy in ways most organizations do not understand, partly because the connection of literacy and bureaucracy has remained largely under-theorized and thus the framework for interpreting the effects of new technology does not exist.

Literacy, to the extent it penetrates a society, thus creates an information regime, that is, a mode of order not only dependent on information (as all human societies are, whether oral or literate), but one centered around institutions of information and information itself as a form. An information regime rests upon the inseparable transformation of society involved in the reconfiguration of space and time made possible by literacy.

Since literacy fundamentally recreates the formal and material possibilities of the human species by rendering knowledge temporally and spatially independent of its originator or user, it creates the possibility of new institutions and social forms and gradually erodes the characteristics of oral societies.

If information can only be stored in the mind of a living person, and can only be accessed through their speech, the spatio-temporal constraints on information are profound, as they require inhabiting the space and time of another person while they are speaking. This not only requires physical proximity, but one has to be socially connected to the source of the information, particularly if one wishes to have voluntary and regular access to it.

It is worth pondering deeply the implications of this congruence between sociality and information access, for it specifies an anthropological feature of oral societies: access to information is not only socially regulated; information and its flow are inseparable from social institutions and relations. Beyond the obvious fact of an expert being unavailable while sleeping or hunting or talking to someone else, the identity of social networks and information networks means that one’s capacity to access information is a function of one’s standing in the group. Hence, the young, prior to initiation, are forbidden access to central knowledge of the society; access to that information both derives from and partially constitutes the rite of passage to adulthood.

Literacy is inadequately understood when we think of it merely as an instrument or communications tool; literacy, in changing the nature and flow of information, is a plastic (as opposed to rigid) social form that functions at a cosmic or anthropological level: it inevitably reorganizes and even revolutionizes human beings, their cultures, tools, and self-understanding.[ii] Its plasticity derives from the fact that the tools of literacy (e.g., tablet, scroll, codex, printed book, computer) change social forms depending on their nature and their interactions with the existing ecology of the culture and its historical and technological status and depending on the nature of their extent of adoption. Mass alphabetic literacy constitutes perhaps the most substantial human revolution in recorded history.[iii] The spiritual origins and context of this fact are crucial for its detailed interpretation, but they can be set aside in this context.[iv]

Literacy, particularly the more affordable its material form becomes, separates information access from social or economic status, redefining both in the process. Social organization can become more complex and varied as its forms no longer have to do the work of preserving and transmitting all the essential information in a society, while information itself can for the first time begin to be imagined as something distinct from a person and the whole social organization.[v]

In a way that is difficult to imagine, literacy creates the possibility of the thought of knowledge as such. We cannot unthink this thought, just as we cannot represent being illiterate once we are literate. It is our native idea of knowledge, encoded into the distinctness of both of those terms (idea and knowledge); what is hard for us, as literate people, is to imagine knowledge not being its own distinct category.

But for an oral people, the representation of a specialized domain that is not intrinsically linked to the people and its stories, for example, could not occur. Literacy makes possible the idea of the idea (the origins of the idea of the idea, the literal mother of all ideas, is one of the most important and currently untold human stories—but from the idea we get the apparently pure “material conceptuality” of Capital). From the idea and a distinct concept of knowledge, the eventual emergence of the category (not word) myth also emerges.

We literally see knowledge externalized in a material form, all by itself, anytime we look at a book, or a page, or a computer. This makes possible the illusion that knowledge just is identical with its external expressions, its tools, which is precisely what Plato is concerned about in the Phaedrus. Such an illusion makes practically inevitable, from a psychological standpoint, the mistaken assumption that our idea of knowledge is somehow independent of our literacy, our technological context in the broadest sense. This illusion of the independence of our modes of representation from technology in turn creates the delusion that our way of thinking of reality is normal, or given, rather than a historical effect of a most extraordinary and complex process. To see something as normal is partly an experience of psychology, when we mean by normalcy “familiarity and commonality.”

An effect of the perception of normalcy is the unthinking projection of the experienced “normal” as a rule or criterion onto contexts to which it is foreign and therefore inappropriate (in history, this is called anachronism; in anthropology, ethnocentrism; in short and in everything, it is a profound and almost unavoidable error). Part of the nature of education is to convert the perception we have of things derived from mere psychology (e.g., I have experienced this constantly, so it is normal) into an informed representation of things in the context of their origin, development, mode of existence, and possible transformations; educated perception sees not only the present, but sees in the present its origins in the past and thus a sense of determinate future possibilities as well. With respect to history, we call this historicizing, or we speak of putting things in a “social” context when drawing primarily on sociological or anthropological frameworks, and, mutatis mutandis, for other areas. It is essential we do this with technology itself, or else we can achieve no perspective from which to consider its actual meaning and significance.

In separating knowledge or information from sociality, and thus direct dependence upon another person speaking, literacy affects a revolution in the most general yet profound axis of human life: our relationship to space and time. (When referring to these in their mutual connection, I will use “spatio-temporal”). To grasp this in its elementary form, which will suffice for our purpose, we need to recognize that all humans exist in a spatio-temporal framework that is a complex creation of their language, culture, worldview, and technology.

To put bluntly what literacy enables, and eventually effects, we can say that it makes possible the separation of space and time. In other words, it creates the possibility of spatio-temporal frameworks characterized by modes of spatial and temporal autonomy. Space and time, in this sense, still are always interacting and must eventually be thought together, but it is crucial to see, if briefly, what their separation means.

An oral society has no written calendar—this is self-evident. Thus all temporal representation can only occur through speech and is indexed to perceptible changes in nature (especially solar and lunar changes) rather than an abstract function, like counting. Time-keeping will be relatively simple as a consequence, and will be communal, part of the society’s self-understanding, connected to its myths and rituals. The individual does not, properly speaking, keep time personally but participates in time collectively. Time, its measurement and social significance, is thus inseparable from speech, and consequently from people and from space—in short, from the whole shared culture. To discourse about time, to think about time, to talk about time, will involve sharing in social life. To be spatially separated to an extreme degree from one’s group in such a context threatens loss of one’s identity, including the capacity to experience time as a social reality, which occurs through the group and its collective action.

The representation of space and time are both bound to the medium of representation itself, namely the living, speaking person as a member of the community. Sharing space requires sharing time. So in an oral society there is a strict spatio-temporal framework in which temporal acts take on significance only through their social significance, which requires shared space with others, or through their production of an artifact or product that witnesses the process of time—such as the slain animal from a hunt or a piece of pottery. Information itself cannot be rendered person-independent, and thus informational activity is restricted to a common spatio-temporal framework: in this sense, oral cultures existing in so-called “mythic” time, which Mircea Eliade saw as characteristic of archaic societies, should be understood as a necessary feature of their technological situation.[vi] That moderns consider such societies to be “mythic” is our projected awareness that we find such cultures, their activities, and their sense of reality deeply unfamiliar yet entrancing. This is because we have been technologically torn away from the inseparability of land, customs, space, time, and language that makes up the matrix of oral culture.

Literacy, in creating a separable, separated, and thus externalized artifact of the mind, splits space and time. A temporal activity can produce an informational effect without sociality directly entering into the production process (we know, as a matter of fact, that it took a very long time for literacy to separate itself fully from oral patterns and habits, but our purpose here is to achieve schematic and conceptual clarity, not detailed historical knowledge), which means in turn that information is for the first time rendered spatially and thus temporally independent of its originator. The artifact, whether a scroll or book, becomes a proxy for the embodied speaking of its creator.

One must share space and time with a material artifact, but not the person who created it. This itself is a dramatic form of specialization. Information is literally rendered into a distinct and potentially autonomous material form, and in that sense, we can see literate technology as the creation of the distinct information or knowledge sphere.

And “distinct” here means also separate. The conceptual distinctness of information emerges as a product of the literal spatio-temporal separation of the creator from the creation. The proxy status of literarily encoded information is weak, in relation to issues of authority and interpretation, compared to an oral source, which, if misunderstood, could directly correct the listener. But, as Socrates says, writing can’t talk back.

It is crucial to note a fundamental ambiguity that literacy creates through this separation of knowledge and its expression in an artifact. Literacy makes possible the confusion and conflation of knowledge as a skill or virtue inherent in the mind of people, which is the original sense of knowledge through most of its history (the Greek epistēmē and the Latin scientia from ancient philosophy until the modern world referred to a condition of the mind or soul, not primarily something external, like an artifact, such as a book),[vii] and knowledge as a representational artifact, like a text, that expresses and externalizes knowledge. We can call such artifacts proxy-knowledge, that is, they represent potential knowledge to a person with a rightly informed capacity to actualize it.

We now think the opposite of the way our culture has thought through most of its history. For we regard terms of knowledge, including information, data, etc. as primarily abstracted collections stored in media external to the originators or users, that is, we conflate artifacts of proxy-knowledge (books, programs, etc.) with actual states of mental skill and power. The idea of knowledge as a virtue, in the sense of a skill or power of the mind, sounds very strange to us. Yet this is still true and is theoretically what education produces: a state of informed mind, among other things, capable of deploying dynamic skills in varied situations.

Yet we speak of the “knowledge at our fingertips,” as if any real knowledge exists apart from the subjective formation of individual human minds. Search engines are useless or worse as an informational resource to a person who is semi-literate and lacking any training in the sorting and acquisition of reliable information. Without being literate and understanding research and the different values of various information sources, for example, modern search engines are totally incapable of being informative. This points to a crucial fallacy in modern society, connected particularly today with computers, namely, the fallacy of collective knowledge.

“We,” strictly speaking, know nothing. Collective knowledge as a useful term may refer to at least two conditions: (1) the condition of widespread knowledge that most or all members of a group possess as individuals, and may thus assume as background, use for references and allusions, and draw on in other social contexts. And (2) a body of knowledge whose full extent is incapable of being contained in a single person and has to be distributed over a group of interrelated specialists. This is the case with scientific knowledge, for example, where a shared and advanced core disciplinary knowledge serves as the foundation of ever more specialized subfields and research programs. Scientists can thus speak of what “we” know, meaning the field in question, not what any one scientist in the field has scientific knowledge of—rather, each individual relies on reports by colleagues for the vast majority of their knowledge, which means, psychologically, a dependence on testimony while possessing first-hand knowledge only of their own specialized area.

In both cases, collective knowledge depends upon individuals each learning a shared body of information, and in the scientific case this shared body becomes the basis for linking together different specialized areas. In no case does there exist knowledge that is shared across a group that is not individually present in the minds of those who constitute the group. The fallacy of collective knowledge, then, refers to speech and behavior that assumes or represents knowledge as collective independently of the question of how many individuals actually do know, or could reasonably be thought to learn, the potential knowledge in question.

Thanks for reading.

This post was an excerpt from Underground Theory: Coming To A City Near You. Enjoy it serially here for free. If you prefer a physical copy, orders within the U.S. can get it at a discount here. Otherwise, I recommend getting it from Amazon. Also, stay tuned for the Audible and e-book version of this - in production now!

Get involved: If you want to get actively involved with ongoing lecture sessions related to timenergy research and critical media theory, become a TU subscriber today here. TU Subscribers also get a PDF of Underground Theory.

Support: If you don’t have time to get involved but wish to support nonetheless, become a patron here.

Samuel Loncar, Ph.D. (Yale), is a philosopher, artist, and editor curating and creating new knowledge at the intersection of science, religion, art, and technology. He practices philosophy as a way of life and integrates scholarship, consulting, and institution-building. His work has been translated into Chinese and Farsi and taught at universities across the world, and he has partnered with clients like the United Nations, Oliver Wyman, and Red Bull Arts.

He is the Editor of the Marginalia Review of Books, Director of the Meanings of Science Project, founder and creator of the Becoming Human Project, and the host of Becoming Human: A Podcast for a Species in Crisis. | www.samuelloncar.com

[i] My concern is not with bureaucracy as it evolves over time, but in the way in which literacy creates its very possibility. For the traditional and classic overview of bureaucracy, see Max Weber, From Max Weber, ed. and trans. H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (New York: Oxford University Press, 1946), 196 ff. Cf. Alfred Chandler, Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1994).

[ii] Cf. Walter J. Ong, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word (New York: Routledge, 1982); Colin Wells, “The Coming Classics Revolution, Part I: Argument,” Arion 22.3 (2015): 37-80; idem., “The Coming Classics Revolution, Part II: Synthesis, Arion 23.2 (2015): 95-145; Eric A. Havelock, The Muse Learns to Writer: Reflections on Orality and Literacy from Antiquity to the Present (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986); Paul Saenger, Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997); Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Theory Underground to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.